A study led by archaeologist João Zilhão, from the University of Lisbon, reveals “precise conclusions” about the way populations inhabiting the Portuguese territory, from about one hundred thousand years ago to about ten thousand years ago lived their lives.

The conclusions released today by the Centre for Archaeology of the University of Lisbon (UNIARQ) come from the analysis of the chemical composition of the enamel of fossil teeth from the excavations near the source of the river Almonda, in the Terras Novas region, that allow scientists to understand the people who lived there.

The study reveals “precise conclusions about the way of life, territoriality, and subsistence of the populations that inhabited the Portuguese territory during the last glaciation, between about 100,000 and about 10,000 years ago.”

Developed in the system of archaeological deposits associated with the source of the river Almonda, near Torres Novas, in the district of Santarém, by researchers from the University of Lisbon Archaeology Centre, and the universities of Trento (Italy) and Southampton (United Kingdom), the study was published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the official journal of the Academy of Sciences of the United States.

“The study represents a milestone of great importance for Archaeology, demonstrating how, even for very remote times, there are today scientific techniques that allow us to approach people’s lives at the scale of the individual, not only that of the population,” UNIARQ highlights.

The researchers analysed the chemical composition of the enamel of the fossil teeth of humans and animals from excavations at the source of the Almonda River, which have been carried out since 1988, UNIARQ says.

According to the statement, “In rocks, strontium isotopes gradually change over millions of years due to radioactive processes. Therefore, the strontium content of soils varies from place to place depending on the antiquity of the geological substrate. This isotopic ‘fingerprint’ passes from the soils to the plants that grow in them and through them into the food chain, eventually being registered in the enamel of the teeth.”

The “comparison with the strontium content of the teeth allows us to reconstruct the territory travelled by individuals, whether human or animal, during the period of enamel formation, which, for the human teeth were two premolars and one molar, aged between five and fifteen years.”

The archaeologists used a technique that used laser sampling, “which allows us to take and measure samples along thousands of points selected according to the growth axis of the tooth crown.”

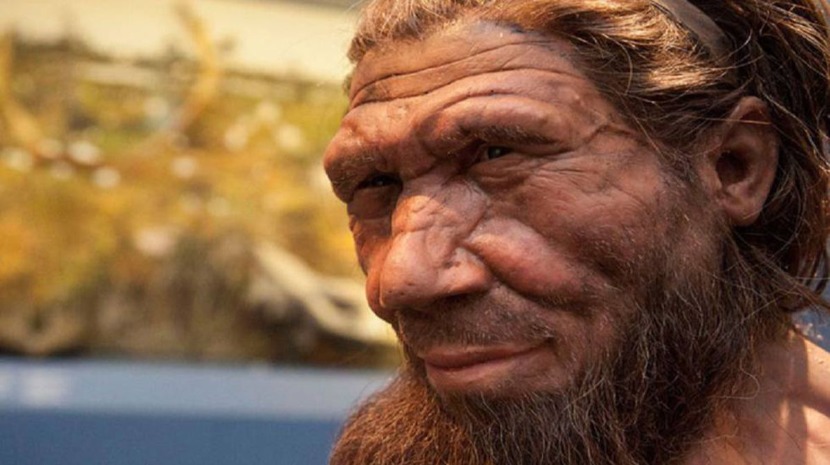

Regarding human fossils, the samples were obtained from two teeth of Neanderthals from the Middle Paleolithic, about 95,000 years old, found in the Gruta da Oliveira, and one from the late Upper Paleolithic, about 13,000 years old, found in the Cistern Gallery.

“Using the same technique, we analysed the strontium isotopes in the tooth enamel of rhinoceros, horse, deer, and mountain goat remains from the two deposits and still another belonging to the same system, the Lapa dos Coelhos.”

As for the remains of game, “the levels of oxygen isotopes were also measured, which vary seasonally from summer to winter.” Thus, according to the same source, it was possible to determine animal migration and to establish at what time of the year they frequented the different pasture territories.

“The results show that in the case of Neanderthals from about 95,000 years ago, the mountain goat was hunted in the summer, while horse, deer, and rhinoceros remained present in a radius of 30 kilometers around where they could be hunted throughout the year.”

In the case of the individual of the late Upper Paleolithic, about 13,000 years old, “subsistence was obtained in a more restricted area – the approximately 20 kilometers of the right bank of the river Almonda, between the source and the confluence with the Tagus – and the place of residence alternated seasonally between these two extreme points of the territory.”

Deer remained the predominant game, but also included in this was mountain goat, and small prey such as rabbits and freshwater fish.

At this time, the land turtle, much consumed by Neanderthals, was already extinct in the Portuguese regions, so it does not appear on the menu, the statement said.

“It is likely that the difference in territory size between the Neanderthals of the Middle Palaeolithic and the Magdalenians of the late Upper Palaeolithic is related to demography. With a lower population density, Neanderthals could dispose of larger territories. In Magdalenense, the increase in population density forced human groups to extract their subsistence within smaller territories, and hence the fact that small prey and river fish were exploited more intensively,” explains João Zilhão, co-author of the article, cited by UNIARQ.

Samantha Gannon

info at madeira-weekly.com

Photo: JM